Summary of field work 2002-3

By John

Gale, Paul Cheetham,

Joanna Laver and Claire Randall

A

second season of field evaluation took place between 4th

August and

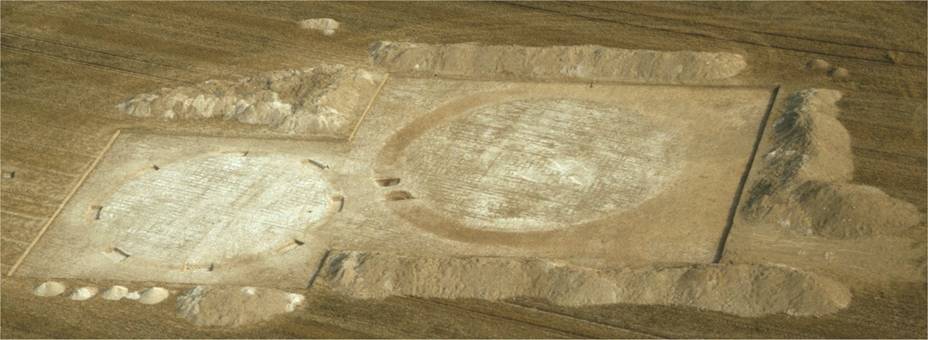

Fig 1

Area

excavation of Barrows 1 and 2 photographed from the air in September

2003. ©

John Gale

Introduction

As

part of the research design brief for the Knowlton Project (Gale 2002,

Gale

2003) concerning the evaluation and quantification of prehistoric

settlement

and associated activity within the Allen valley of East Dorset,

attention has

been partially focussed on the extensive barrow cemeteries that

dominate the

valley. Several concentrations of round

barrows (mostly surviving only as groups of ring ditches in an

archaeological

rich prehistoric landscape that has been devastated by intensive arable

farming), occur over a 5km stretch of the Allen Valley between the

Knowlton

complex to the north, and the High Lea farm Group to the south. Very little is known about any of these

funerary monuments beyond those general assumptions drawn by analogy

with

examples studied elsewhere in

The

clear foci for the funerary monuments within the

Whilst

the greater concentration of barrows within the Allen valley appear to

be

located around the Knowlton Henge complex

their

distribution would seem to extend from here to the south, mainly in

linear

groupings more or less following the line of the river Allen. The end of these concentrations would appear

to be found at the High Lea Farm Barrow group between the villages of Witchampton and Hinton Martell.

As

with the majority of barrows in the Allen valley the High Lea Farm

group is

extremely poorly preserved with only two of the group surviving as

upstanding

earthworks. However, both of the

surviving barrows owe their partial conservation to their location

within the

headlands of the field known as Kings Close where the plough is

frequently

lifted and turned and therefore consequently is subject to a lesser

degree of

damage. Elsewhere in the field the presence of numerous ring ditches

are

attested through crop marks visible on aerial photographs.

One such photograph (NMR 4437/04, SU 0006/8)

taken obliquely when the field contained a crop of pea in 1989,

illustrates a

dense concentration of ring ditches and other maculae which appears to

represent a definable cemetery group of ploughed out barrows,

consisting of at

least three distinct linear groupings.

Whilst

such evidence attests to the presence and location of an extensive

barrow group

it provides little effective information as to the sequential

chronology, or

nature of the barrow clustering. In

addition, whilst the barrows have had much (if not all) of their above

ground

features destroyed, the survival of below ground features (grave cuts,

earth

fast cremation urns etc.) remains undetermined. With these factors in

mind it

was decided to initiate a two step evaluation of the cemetery contained

within

Kings Close over two successive seasons commencing in 2002.

During

the examination of the aerial photographic evidence available at the

National

Monuments Record centre at

Kings Close evaluation - step 1 (August – September 2002)

During

a four-week period a programme of fieldwork was instigated to explore

the

location and survival of archaeological features associated with the

known

barrow group at High Lea Farm. The 15ha field known as Kings Close was

subjected to an extensive programme of Geophysical analysis using a

range of

techniques and equipment to both locate and explore the surviving

features of

the barrow group (see below). In the

wake of the geophysics programme a sample area of the field was defined

to

assess the extent of archaeological material within the current plough

soil and

to examine if the barrows were still being actively disturbed by the

arable

regime.

Test-pitting 2002

A

total of 67 (1m x 1m) test pits were hand excavated over an area of

25940 sq. m

located in the north of Kings Close. The

sampled area was chosen to maximise the range of features evidenced by

both the

geophysics results (see below) and those contained within the aerial

photograph

(NMR 4437/04, SU 0006/8) taken in 1989.

The test-pits were placed systematically within a grid and were

spaced

at 20m intervals.

After

marking out each test-pit was hand excavated and the plough soil was

removed

and screened through a 6mm-mesh sieve.

Soil layers and or features below the plough soil were not

excavated but

when present were contextualised and recorded.

With few exceptions the plough soil (defined here as the last

cultivation horizon resulting from the 2001 ploughing of the field),

lay on top

of a further soil layer largely differentiated from the uppermost soil

by a

larger quantity of chalk within its matrix.

In all likelihood this soil is probably an earlier plough soil,

the

result of an episode/s of deeper ploughing in recent times.

Material

recovered from the active plough soil throughout the test-pitting

exercise

consisted of minimal quantities of cultural material mostly comprising

of

relatively modern ceramic material (brick, tile and small quantities of

earthen-ware, which are probably of Verwood

types. With the exception of a singular

flint tool (an awl), material dateable to the late Neolithic or the

early-mid

Bronze Age consisted of a few struck flint flakes with no evidence of

prehistoric pottery having been recovered.

The

excavation of the test-pits failed to find any clear evidence that the

barrows

were being actively destroyed at the present time and certainly no

material was

recovered within the plough soil to indicate that funerary deposits

were being

actively destroyed.

Test trenching

2002

Alongside

the systematic sampling strategy employed to evaluate the surviving

archaeology

at the site, limited trial trenching was applied in targeted areas

where

specific features were identified as having survived evidenced by the

results

of the geophysical survey (fluxgate gradiometry). Two adjacent barrows were chosen for further

investigation and prior to excavation both barrows were subjected to

further

detailed geophysical investigation (see Geophysics below).

To confirm the presence of the ring-ditches

of both the chosen barrows and to tentatively explore the area bounded

by the

ring ditches two small excavation trenches were aligned to cross each

of the

barrows ditches. The trial trench located on the smaller of the two

barrows was

subsequently extending to its centre. At

this stage the intention was to confirm the presence of archaeological

deposits

only, with the option to excavate being part of a later phase of

investigation

(Step 2 below).

Trench 1

Trench

1 was positioned on the larger of the two barrows and was 1m wide and

8m

long. The modern plough soil was removed

from the trench by hand and was screened through a 6mm sieve. At the base of the plough soil only two

contexts were recorded, the natural bedrock and the fill of the barrows

ditch. The barrow ditch fill was

approximately 1.3m in width and was bounded on either side by weathered

chalk

bedrock in which the scoring marks of the plough could be clearly seen. Materials recovered from the plough soil were

small in number and consistent with those from the test-pits – there

was no evidence

of funerary deposits either in situ

or disturbed.

Trench 2

Trench

2 was positioned on the smaller of the two barrows and consisted of an

‘L’

shaped trench. The longer primary axis of the trench was 10m in length

crossing

the barrow from outside of the ring ditch ending at its approximate

centre

where a 3m extension was excavated perpendicular to the main axis. As

with

Trench 1 the plough soil was removed by hand and screened through a

6mm-mesh

sieve. Material recovered from the

plough soil was similarly consistent with previous examination of the

plough

soil elsewhere on the site, with no evidence for funerary deposits or

material. As with Trench 1 the presence

of a soil fill that bisected the excavation trench, is entirely

consistent with

the ditch predicted by the geophysics results. This ditch fill was

approximately 0.75m wide and was bounded internally and externally by

plough

damaged natural chalk.

Trench 3

In

addition to the trial trenching of a sample of the known barrow

population

within the group a third trial trench was instigated to examine the

anomalous

results provided by aerial photography and geophysical investigation in

the

north of Kings Close. Whilst aerial

photography determined the presence of a number of maculae in the north

of the

field which appear as crop marks consisting of ‘filled’ circles they

did not

similarly register on the magnetometer survey of the same area. Whilst it could not be discounted that these

features were possibly pond barrows (the aerial photograph identifies

at least

five similar anomalies) it seemed that they were much more likely to be

geomorphological in origin.

To further explore these features Trench 3 was located over one

of them.

The trench was 10m long by 1m wide.

As

with previous trenches all of the plough soil was removed by hand and

screened

through a 6mm-mesh sieve. Below the

plough soil a well-sorted humic soil was

encountered

over the whole of the trench, which was systematically removed by hand

and

screened. The depth of this deposit was

nowhere greater than 10cms and it appears to be an earlier agricultural

horizon

that had survived recent plough activity because of the greater soil

depth in

this part of the field. Below this layer a further continuous layer of

soil was

found which was remarkably chalk free. A sondage was

excavated

in the north-western corner of the trench to explore this soil and 0.6m

of it

was removed without encountering any change in the deposit. It would appear that the deposit is a colluvial soil fill, part of a much deeper

deposit that is

probably natural in origin and is almost certainly a doline/sinkhole,

not an uncommon feature in areas where the cretaceous chalk beds are

closely

associated with Tertiary sand and gravel deposits (for a discussion on

the

formation of Dolines in Dorset see House

1991). The colluvial

deposit contained, as one might expect, a chronological mix of cultural

materials with pottery being the most numerous material recovered. The fabrics noted consist of later earthen

wares (of Verwood types) and also

fragments of later

prehistoric material albeit in relatively small quantities. The trench was not excavated beyond a depth

of 1.2m below the modern ground surface.

Kings Close evaluation - step 2 (August – September 2003)

The

programme of archaeological investigation instigated in 2002 had

clearly

established the presence and location of surviving in-situ

archaeological deposits within the High Lea Barrow Group

but the extent of survival was as yet weakly defined.

Step 2 of the evaluation process, instigated

during the late summer of 2003, was targeted to investigate a sample of

those

known deposits via the area excavation of the two ring-ditches

(barrows) that

had been the subject of the trial trenching in the previous season

(fig.,1, 2

and 3). In addition, further geophysical

investigation was undertaken within Kings Close, to complete the area

survey

and to apply complimentary techniques to defined ring-ditches in an

attempt to

draw as much information as possible from the surviving archaeological

deposits

(see below).

Area excavation of

Ring –ditches

An

area of 1043 sq. m was marked out for excavation to contain the two

adjacent

barrows sampled in the previous season’s fieldwork.

Having previously determined the

archaeological characteristics of the plough soil it was subsequently

removed

by machine, down to its interface with underlying deposits. Over the western half of the excavation

trench the plough soil overlay natural chalk with the exception of the

soil

fill of the surviving ring ditch. Whilst

the western quarter of the larger barrow was similarly exposed by the

arc of

its soil filled ring ditch the eastern two thirds was covered by a thin

layer

of soil. This soil layer, which clearly

lay over the ring-ditch fill was probably a

remnant of

an earlier agricultural horizon falling below the plough depth of the

most

recent agricultural activity within the field.

The layer was similar to that encountered within some of the

test pits

of the previous year, and was identical to a similar soil found in

Trench 3

(see above). The greater depth of soils on this part of the site is

most

certainly due to natural fluctuations in the topography of the field,

with some

dips and troughs in the bedrock containing slightly greater depths of

soil.

Such an occurrence is if course partially masked by the topographical

smoothing

effect at the surface caused by such agricultural processes as

ploughing and horrowing.

Ring ditch – Barrow

1

Following

the removal of the overburden of plough soil by machine stripping the

residual

plough soil was trowelled back to reveal a

heavily

plough scarred natural chalk surface.

Also revealed were the surviving remains of the cut and fill of

a

circular ring ditch forming an almost perfect circle 17m in diameter. The width of the remaining ditch was on

average 0.76m. It was decided to

excavate a 20% sample of the remaining ditch achieved through the

placement of

eight box-sections aligned on the cardinal and first level directional

points

of the compass (north, north-east, east, south-east etc.). All eight

box-sections revealed a similar sequence of deposits within a heavily

truncated

ditch that was never greater than 0.3m deep.

The ditch cut was flat-bottomed only marginally narrower at the

base

than at its truncated top. The ditch

fills were uniformly similar, consisting of a primary chalk slumping

occurring

at both sides possibly suggesting that the original barrow may have had

an

outer bank as well as an internal mound. Alternatively this initial

chalk

slumping may have been the result of the collapsing of the upper sides

of the

ditch walls soon after construction, especially so, if as is likely the

ditch

walls were cut to a shear angle. The secondary fills of the ditch

appeared to

the product of the slow filling of the ditch with colluvial

material that contained a relatively high proportion of chalk. The

fills were

generally devoid of artefactual material

although the

secondary fills did produce a small number of heavily gritted but

largely

non-diagnostic pot-sherds which may be

Bronze Age in

date.

It

is clear from the filling of the ditch that it has almost certainly

been

heavily truncated by farming activity over a considerable period of

time. It is a matter of conjecture as to

how much

of the ditch has been destroyed through agricultural activity (and

consequently

the barrow and the original ground surface), but the shallow nature of

the

extant ditch might suggest that in this instance as much as 0.4-0.5m

has been

eroded away since the monument was first erected.

Fig 2 (above) Barrows 1 and 2 partially excavated (2003)

Fig 3 (right) Ditch section of Barrow 1 – partially

excavated.

Ring ditch – Barrow

2

Following

the removal of the overburden of plough soil by machine stripping the

residual

plough soil was trowelled back to reveal a

composite

surface of plough-disturbed natural on the western half of the barrow

with

remnants of an earlier soil on the eastern half of the excavated area.

Approximately

two thirds of the barrow ditch was observable as an arc of soil against

a

largely plough disturbed chalk bedrock.

The soil filled ditch scribes an arc of approximately 22m

diameter with

the width of the ditch being never less than 1.25m.

As the

field was to be brought back into production it was not possible to

proceed

further with the excavation of the barrow that is scheduled to be

completed in

the summer of 2004. However, it is clear

that no funerary deposits remain within the western half of the

interior

surface of the barrow and its close proximity to Barrow 1 suggests that

it will

have suffered a similar degree of erosion.

The ring ditch does have a causeway across it in its

south-western

quadrant which may suggest that it is Later

Neolithic

in origin. The nearest geographical and excavated example of this form

of

monument was investigated by Pitt-Rivers within the Worbarrow

complex near Sixpenny Handley towards the end of the 19th

century

(Barrett et al 1991; Gale

2003a).

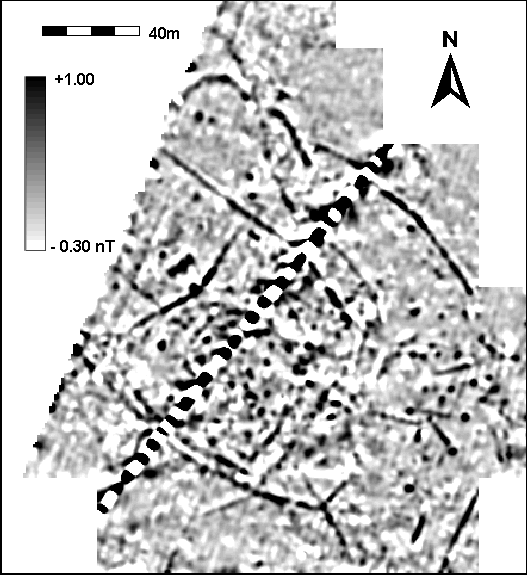

Geophysical Surveys at Kings Close

During

the 2002 and 2003 fieldwork campaigns

Fig 4 Fluxgate

gradiometer survey of Kings Close 2002-3

© Bournemouth University

Firstly,

there is a length of ditch, showing as a dark (positive) linear anomaly

running

south along inside the eastern boundary of the survey and parallel to

the Wimborne to Cranborne

road. Additional short linear anomalies

that may

represent ditches are to be seen entering the survey area in the south,

running

north-east near the smaller single ring ditch, and one entering from

the

north-west margin of the survey area.

The latter is associated with an area of magnetic noise that

corresponds

to a surface spread of post-mediaeval building material noted during

survey.

Earth resistivity survey revealed the

possible

remains of a building in this area of higher magnetic noise, however,

other

than this, taken across the area as a whole, the earth resistivity

survey provided little additional information. High-resolution

(0.25x0.5m)

caesium gradiometry was undertaken over

the group of

three ring ditches to the south west of the oval ditch. This work

confirmed the

presence of an apparent causeway in the south west quadrant of the

central ring

ditch and provided evidence of ongoing plough damage, suggesting, as

excavation

confirmed, that these feature have been severely truncated in this part

of the

site.

Electromagnetic survey was undertaken over the scheduled double ditch

barrow in the south-west of the survey area, the oval ditch, and the

other

surviving barrow abutting the top north-west edge of the survey area

which is

the bounded by

Geophysical Survey at Great Higher

In

2003 only fluxgate gradiometry was

undertaken in

Great Higher, although further techniques will be incorporated in

future

seasons. The results so far (Fig 5), unlike those from King’s Close,

have

considerably improved on the information currently available from

aerial

photography. Compared to the murky outline of a possible enclosure

identified

on the aerial photographs, the magnetic survey has revealed a complex

palimpsest of ditch systems and enclosures that largely defies

interpretation

and phasing from this initial survey. Along with these linear features

is a

scatter of what are apparently pits (one confirmed as such by

excavation)

spreading across the whole central area of the survey.

These pits presumably continue to both the

east and west, but are not detected in any numbers to the south and

north of

the central area that is defined and bounded by the curvilinear

ditches.

Running north-west to south-east through the survey area is the

tell-tale

positive and negative beaded response of a steel pipeline that has cut

right

through the site, presumably without the presence of the remains being

noted. The discovery of building

foundations during excavation, invisible to gradiometry,

requires that earth resistivity, electromagnetics,

and possibly ground penetrating radar, will be employed during the 2004

season

in an attempt to map these foundations prior to any further excavation.

Fig 5 Flugate gradiometer

survey of Great Higher. © Bournemouth University

Trial trenching at Great Higher 2003

As a

result of the initial analysis of the data from the aerial photography

and

geophysical surveys, two trial trenches were instigated during 2003. The larger of the trial trenches (Trench A)

consisted of an ‘L’ shaped trench 50 m long by 2m wide located across

six

boundary/enclosure ditches at the western extent of the field. This trench was thus located to investigate

the nature, extent and possible date of a maximum number of possibly

inter-related boundary ditches, three of which were aligned parallel

with each

other and closely spaced. The plough soil from this trench was hand

excavated

with every fifth barrow of soil screened through a 6mm sieve to sample

any

cultural material contained within it.

As with Kings Close the base of the

plough soil

overlay for the most part natural (plough damaged) chalk bedrock except

in

those areas where the upper fill of six ditches were recovered. The

resultant

ditch sections, with one exception, contained within their secondary

fills

quantities of domestic pottery largely comprising 1st – 3rd

century AD Black burnished wares and likely regional variants of

similar coarse

wares. Occasionally this pottery was

mixed with other domestic debris such as occasional tesserae

and other ceramic materials, as well as oyster shells, all of which

appeared to

be indicative of settlement debris that had fallen into the ditch

rather than

having been thrown in, or otherwise deliberately placed within them. It is likely that the material has washed-in

perhaps after the settlement was abandoned and the land was brought

back into

production at as a yet undefined date.

A

smaller trench (Trench B -8m x 1m) was

located within the centre of the complex of ditches, placed over a

section of

an enclosure ditch which seems to demarcate a ‘D’ shaped enclosure of

approximately 0.4ha and also over what appeared to be one of many ‘pit’

like

features in its interior. This trench was only partially excavated but

an

enclosure ditch was exposed as well as a short length of walling

material

(un-coursed flint rubble) within which were found two bow brooches that

are

possibly 1st –3rd century AD in date. The presence of unexpected in situ

walling material in this trench

necessitates that further geophysical work be undertaken on this site

before

further excavation takes place.

Future work

In

the light of the preliminary findings from two seasons of work

summarised here

plans are now in place to complete the excavation of Barrow 1 in Kings

Close

and to further explore the likely Romano-British settlement complex at

Great

Higher during the summer of 2004.

Acknowledgments

As

this project currently resides in part within the research led teaching

initiative of the archaeological provision at the School of

Conservation Sciences

at Bournemouth University, much thanks is owed to over 60 students

(undergraduate and post-graduate) who have thus far taken part in the

two

seasons of fieldwork. In particular, gratitude is owed to the student

supervisors Phillip Dunn, Martin Blake and Tracey Minall. To our colleagues Dr Ellen Hambleton, Dr Kate Welham,

Dr

Helen Smith, Jeff Chartrand, Damian Evans

and Bronwen Russell, thank you for your

continued help and

support.

Any field project is indebted

to the support of the landowners that its investigations affect, and in

this

instance we are fortunate to have the support and assistance at High

Lea of Sir

Richard Glyn and particularly the estates

manager Mr

John Maidment and his staff.

Contents

- Background

- Field School

- Opportunities to participate 2005

- 2005 Application form

- Summary of field work 2002-3

- Summary of field

work 2004 (forthcoming)

- Excavations at Knowlton southern henge 1994

- Photo gallery (forthcoming)

- Bibliography

This page was

written and compiled by John Gale,

Last revised: Date